|

Folklore - Ancient Crafts

|

|||

|

Raki production or kazánisma

|

|||

|

The production |

| When

you have only one week of autumn holidays at your disposal, it can be

quite difficult to come into contact with the people who distil. As

distillation mainly occurs within three weeks (number 42, 43 and 44) and

is depending on the weather, you can easily experience, that the time of

distillation falls outside the period of your stay. And as the

distillation itself as already mentioned is not surrounded by any kind of

special festivity, it can be difficult - well, almost impossible - to get

information about where, when or with whom the distillation takes place.

|

|

|

| Raki

is a distillate of the mash (stalks, skins etc.) from the wine production.

First the grapes are pressed for the wine, and then the mash is left in

big containers for about a month - depending on the weather. Of course you

have to take care that the mash does not begin to ferment or rot, as no

chemicals or other things, which may delay the process, are added.

|

|

|

| I

have been lucky enough to experience two distillations, both of them in

the county of Chania, first time in a village a little south of Vrises and

second time in a village near Alikianos. |

||

|

|

||

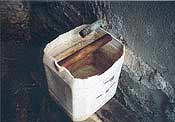

| At

Vrises Christos had a copper (kazáni)

of about 100 litres. It was built into a rather funny looking construction,

which was meant to make sure of sufficient heat and tightness. But let him

tell about the process himself:

|

||

| In

the old days we used olive wood as firewood, but nowadays it is cheaper to

use waste from the olive production (pirínas).

Underneath the kazani I have provided the fireplace with a fan motor,

which increases the heat many times. It is more economical and makes the

process easier too. Before I put the mash into the copper, I place some

dried sprigs of thyme at the bottom. They prevent the mash catching.

Moreover they add taste to the raki, so according to your taste you might

use other sprigs or herbs. Then I add about 100 litres of mash, which I

stamp hard before the lid is put on.

|

|

|

| The

lid is hemispherical with an opening in the top and made from copper as

well. In the opening is mounted a several metres long pipe, where the

vapour is lead forward through a big vessel with water to cool the vapour,

which continues and then runs out through a small pipe into a "slightly

used" plastic bucket. To avoid the vapour from slipping out, all the

joints are sealed up with "zými": a mixture of flour, ashes, cement and water. Because of

the heat the mixture dries with lightning speed and creates a tight

membrane, which on the other hand can easily be broken open, when the

copper has to be emptied and refilled for the next distillation.

|

|

|

| After

half an hour the first drops begin to drip out. At the beginning it is the

so-called "protoráki", which is to strong to drink, but already after

half an hour the raki reaches a more human percentage of alcohol. The

distillation takes about an hour, until almost mere water is coming out of

the pipe, as the percentage of alcohol is going down more and more during

the process.

|

|

|

| The

strong protoráki may be kept in the distillate to keep up the percentage

of alcohol, or it may be saved and used as a massage fluid at common-cold

symptoms - which would often be the case in former days.

|

||

| The

outcome of the 100 litres of mash was about 20 litres of drinkable raki.

Of course a considerable amount of boiled mash is gathered during the

distillation period, and I imagined that it would make a splendid animal

feed, but no - I was lectured - the animals do not want to be bothered

with it. Instead it is used as manure for the olives.

|

|

|

| Not

all grapes are suitable for distillation. The dark grapes are the best, as

they give a much larger percentage of alcohol and in this way a larger

return.

|

||

| In

the old days raki was also made from figs and mulberries, but -

unfortunately - only a few "connoisseurs" carry on this

tradition.

|

||

|

|

||