|

Folklore - Ancient crafts

|

|||

|

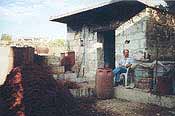

Raki production or kazánisma

|

|||

| Introduction | The social surroundings | The production |

| Having

experienced and read about other more or less joint working processes

going on in the villages of Crete, I must admit that I expected the

distillation of raki to include a lot of festivity, music and partying.

But the world of reality was quite different. In Chaniá and the other

bigger towns they have raki celebrations with music and free raki, but in

the villages nobody makes much of the distillation. Usually a small group

of people meet (each of them might have delivered the material for the

distillation i.e. the already pressed grapes: the mash (stráfylo) which is then being distilled). In all fairness I have to add, that

the two places where I attended the process were very small.

|

|

|

|

|

| Of

course not all Cretans distil raki in autumn. It is most definitely a

phenomenon, which takes place in the country, and even here only a few

people have a still (kazáni). Moreover,

you must have a personal licence issued by the

customs authorities every year. The licence follows the name of the one

who originally got it, but in practice it means, that one of the sons

takes over the work to avoid the paperwork of getting a new licence. In

addition to stating your personal data, you have to report the amount of

mash you have (and therefore pay tax on). As the licence moreover is

limited in time analogous to the mentioned amount of mash, it means a very

concentrated job for the producer. Unlike in Denmark the "snaps"

in Crete is taxed with only roughly 0,55 € per litre, but like everybody

else the Cretans do not like new taxes. It reminds me of the old Danish

expression "snaps of the pauper", an expression which long ago

has lost it's relevance. In this context you must remember that this tax

is fairly new. It was introduced for the first time in 1998 but rises

gradually every year. |

|

|

|

|

| At

the same time as it has become unprofitable for the small

"producer" to make his own raki, quite a few middle-sized

factories have come into existence. They produce large quantities of raki

for tourism and restaurants, but they often add to it different kinds of

additives or maybe even alcohol to keep a certain percentage. This

development means that the previous times, where you in merry company as a

matter of fact were able to consume considerable quantities of raki

without being hit by terrible hangovers the next day, are numbered. And

the taste of the new industrial product, I shall not comment on at all.

|

|

|

|

||